The Unofficial History of AZ4NORML – Part 5

“No Knew Taxes”

Back then, nobody in the legislature would even talk about marijuana legalization, and sometime in 1992 Bill Green garnered the idea of a voter-initiative to change the law. We didn’t have the funds to pay for signature gathering, but there was a lot of volunteers and a lot of enthusiasm, so we decided to go for it, aiming to put it on the 1994 ballot.

Bill, being the methodical engineer, and somewhat ahead of the curve on technology, did a search-and-print of every Arizona statute that mentioned marijuana, cannabis, hashish or hemp. Then he brought the whole enchilada to an AZ4NORML meeting, to hash out what to leave in, what to take out. Everything about selling to minors and bringing pot into prisons and schools could be left as-is. The hemp issue we decided to side-step as well. But there was one part of the law no one knew.

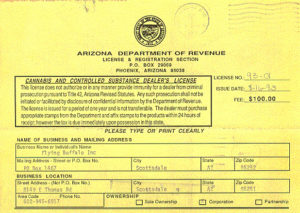

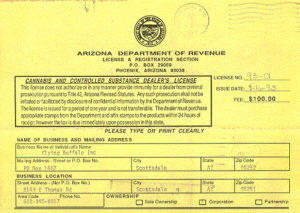

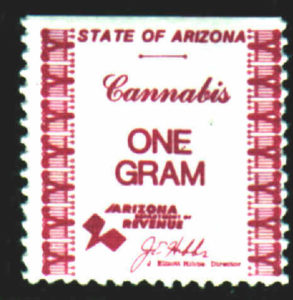

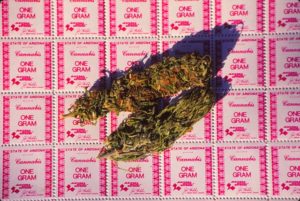

It seems that in the mid-1980s, the Arizona legislature, far ahead of its time, decided to tax and license recreational marijuana use…but they didn’t sell it to the public that way. A wave of drug-taxing legislation had swept the country. Taxing drugs didn’t mean legalizing drugs; it was just another tool in the war against them. Besides jail-time and fines, drug-dealers would be hit for unpaid taxes. Politicians were not selling taxes as a magic bullet; they were simply another weapon to be added to law enforcement‘s arsenal. Arizona, it its own inimitable way, decided to take it one step further: licensing dealers, who would face additional charges for failure to obtain the license.

Although the logic was twisted, the law itself was well thought out, and fees quite reasonable: $100 for the license; $10 tax per ounce, or 35 cents per gram. The law included provisions for the transition from black-market to legal: a licensed dealer had 24 hours from the receipt of contraband to buy sufficient stamps for the quantity involved, or to affix stamps already purchased. Nice. The quantity that could be grown would increase with time, to act as a buffer, so that the legal market would not explode. Overall, it was a near ideal model for legalization.

There was no discussion over licensing fees, tax-rate, how many plants you could grow, etc, because all those things were already in place in the state statutes. The plan looked good on-paper. It was unanimous. We would use the existing tax-and-licensing scheme. Everybody in the room heartily agreed that he or she would be willing to pay a $10/oz tax if it meant you didn’t have to go to jail. Hey…you can dream. We added virtually nothing. A workable system of licensing, taxation and cultivation had already been crafted by the legislature. Nobody knew they could do such things! The bulk of the initiative was deletions from state statutes [ARS13-3405]: felony penalties for possession and sale of cannabis were deleted. Bill filed the paperwork for a voter-initiative with the Secretary of State, and we set about collecting signatures.

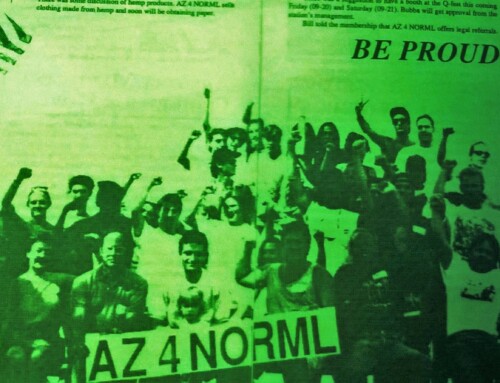

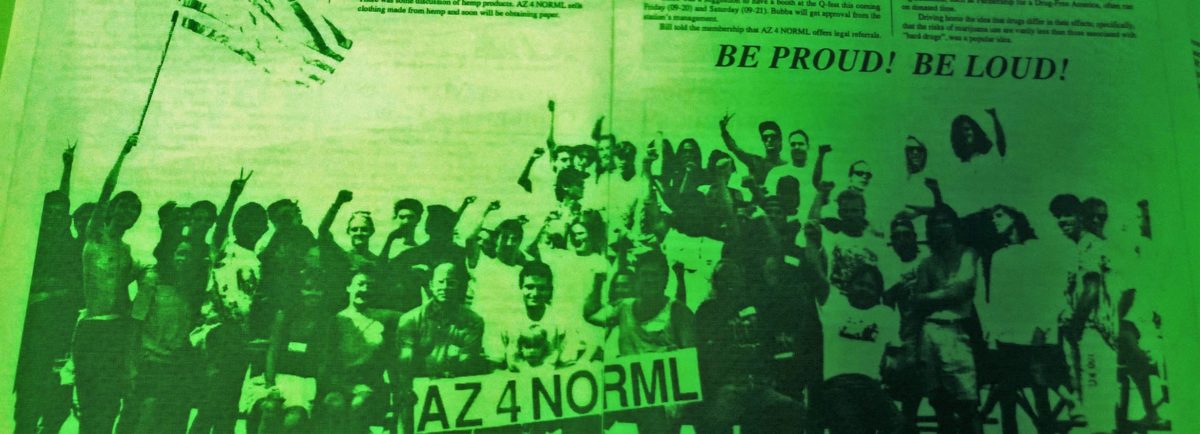

Everybody has their favorite signature-collecting story. It might be the cop that said he would sign it if not in uniform, or the medical doctor, in coat-and-tie with primped wife at the opera house, that did. We combed the usual venues–street-fairs, parades and rock-concerts–and frequently authority figures would try to turn us away. But Bill would hit them with a civil-rights lecture that the ACLU would be proud of, and he always prevailed. We were never forcefully removed from any place that signatures can be gathered, though they often tried.

For some reason, I targeted people smoking cigarettes. Out of all people asked, about 1-in-10 would sign, but of hundreds of smokers I approached, none ever did. Not one. They would say, “I’ve got my freedom…there’s no way I’m sticking my neck out for yours!” Or words to that effect. One rather obese woman, sitting on a bench with burning cigarette in hand, spat out angrily, “No! It makes you fat and lazy.” Oh dear! On several occasions I would persist: “How would you like it if tobacco was outlawed?” Instantly, they would snap back, “Oh I’d love that! Then I could finally quit.”

A surprising number of people expressed the belief that their employers had access to the petitions, and if their name was among the 250,000 valid signatories, they would be out of a job. They must have slept through civics class. One person at a Duran-Duran concert said, “Legalize it? No way! That would take away the special.” Another refused more pragmatically, saying, “No. They’ll just tax it and it will cost even more.” Grateful Dead concerts turned out to be signature dead-zones. Virtually every concert-goer was either from out-of-state or not registered to vote. Never saw that coming.

To my knowledge, a grass-roots, state-wide voter initiative has never been put on the ballot. Only political organizations with pockets deep enough to pay signature-gatherers can get enough signatures to quality. We were on a shoe-string budget. Our efforts were predictably doomed. But somewhere along the way, a short article appeared on page 7 of the local paper: Pot Taxes Declared Unconstitutional. In a Nebraska case, the DEA had busted a local farmer, seized all his assets and jailed him for a long time, then tried to hit him with $100/oz of unpaid pot tax. His lawyer argued, and the high court agreed, that such action represented double jeopardy, and was therefore unconstitutional.

I said to myself, “Okay. If the initiative fails, I’ll get a license, buy the tax stamps–which should remove me from jeopardy–start selling pot, and see what happens.” But I forgot the first law of the land:

Those who make the laws don’t have to obey them.