7: The Fall [link to Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6]

The initial call to the police in August of 1995 set off two countervailing chains-of-events, one good, the other not-so-good. In the first, I got help for my wife; along the second, the narcotics unit of the Phoenix police caught wind of the non-arrest, and made plans to strike back.

The domestic-violence call and its fall-out led to my wife’s two sisters, Linda and Shari, who lived in Michigan, coming out to pay a visit. In spite of all Barbara was going through as a result of the disease, she had absolutely refused to see a doctor, insisting nothing was wrong. With both sisters cajoling her, however, she finally agreed. Take note: family can sometimes provide persuasion where spouses fail. The doctor prescribed Zoloft, and remarkably, she took it without protest. Mood-wise, it was a miracle of modern medicine. She was still stormy, but not violently so, and in between storms, she was the warm, sunny, spring day I had married. I also had help from an angel, but that’s another story.

Yet trouble brewed. The narcotics unit of the Phoenix police department immediately feared the worst, and determined to crush the uprising before it began. About two weeks after making “the call,” I received a knock on my door. It was two detectives from the narcotics unit of the Phoenix PD. They began badgering me with questions about the license and tax stamps. If life had do-overs, I would have said, “I have no idea what you are talking about,” thanked them for their time, and closed the door. But when I answered truthfully, one of them leapt at me like an NFL linesman sacking the quarterback, and the other slapped on handcuffs as soon as the first had me on the ground.

They searched the house and seized the pot, license and tax-stamps…as evidence. Plus a roach-clip, “paraphernalia.” Two felonies, not just one. They took me downtown in the back of the squad car, for the requisite mug-shot, and the famous room without a view. But the room had a lot of people. It was like a human sardine can. In a room made to accommodate about six people, they had stuffed in thirty or more. It was the jail intake; the holding tank. After four or five hours there, they would call your name to be finger-printed. After another four or five hours, they would call your name again, this time to be arraigned. After waiting through arraignment, they put you in a slightly less crowded cell, for more waiting.

The “sardine can” was its own carnival. There was not enough room for everybody to sit, let alone lay down, but many tried to sleep anyway. It was impossible. Everybody was swapping stories and lies about why they were there. The druggies were all coherent, but you couldn’t make out a word the drunks said. One fellow pulled out a joint and waved it around. Considering the search they put you through, that was quite a trick…but they had gotten his lighter. Somebody else offered matches, but the first wanted to save “the J” for a better time. Every ten or fifteen minutes, another squad car showed up to drop off more offenders…excuse me…more suspects.

One, a young, muscular, high-strung fellow with no shirt, was charged with murder. I looked at him incredulously. “I was all looped up,” he explained, as if that justified taking another‘s life. I never did figure out what “looped up” was slang for, but his response followed a pattern that is contrary to the stereotype: he did not deny wrong-doing. Most people who commit “Biblical crimes”–murder, theft and fraud (bearing false witness)–readily admit to their crimes. They know they’ve done wrong, and expect to be punished. That’s why plea-bargaining works to the extent it does.

With the general exception of the men in jail for failure to pay child support, who blamed “the bitch,” of the hundreds of criminals I met in the criminal justice system during my long journey through it, only those accused of victimless crimes denied culpability. Few had called the cops themselves, like I had, but generally those professing innocence had been caught having done noprima facie “wrong.” Due to fate, fortune, bad timing or someone else’s goof, drugs, cops and the accused all wound up at the same place at the same time. Busted…but didn’t deserve it. The lone exception was one guy in for assault. He claimed he had injured someone who was out-of-control. He might have had a case, but aside from that one exception, all the accused I ever met readily admitted guilt.

About 24 hours after my arrest, I was finally released on my own recognizance. A recent storm had taken out the phone line to my house, however, so I couldn’t call home for a ride. I was penniless, needless to say, with no wallet or ID, and ended up walking home, 10 or 12 miles. There comes a time when you thank God for the little things. When I finally got home, it turned out the narcotics detective had failed to detect a half-ounce of “narcotics” in the fridge, and had left me rolling papers as well. Amen to that!

Straight away, I twisted up a fatty and took a much needed “smoke-break.”

[link to Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6]

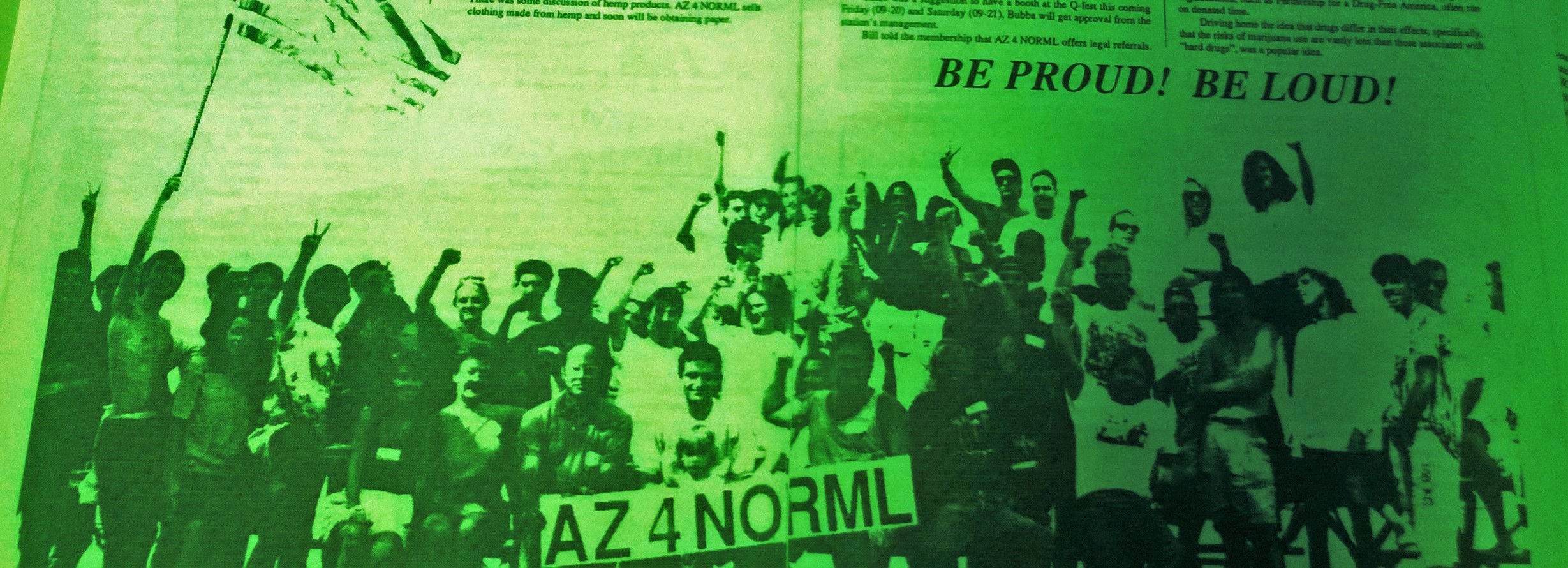

–Peter Wilson was State Director of Arizona NORML during the turbulent 1990s.

[…] to Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8, Part […]

[…] to Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8, Part 9, Part […]